One dimensional array is probably the most important data types in programming languages. First of all, computer memory supports random access and can be treated as a big array. Second, other data structures can be implemented/simulated using arrays, e.g. strings, stacks, queues, binary heaps, linked lists, binary search trees, graphs can all be implemented using arrays. Because of this fundamentality, questions on arrays are commonly asked during a technical interview. The hardness level of such questions may vary from implementing a strcpy function to applying algorithmic tricks. In this post, I will try to cover a diverse set of these array questions, and I will keep this post updated when encountering new problems.

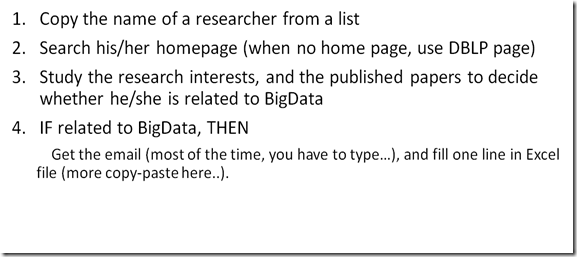

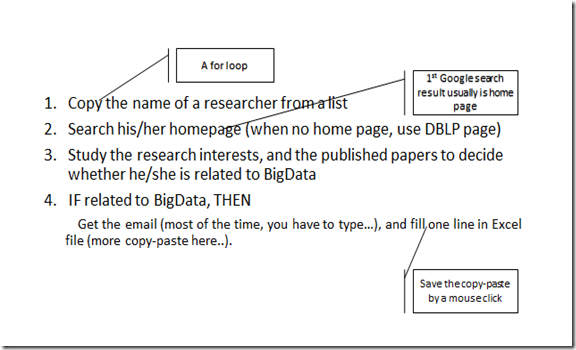

Coding interview questions usually test two aspects:

1. The ability to write correct and stylish programs. The interviewee should write syntactically correct C-family language code, and prove the correctness of the program by checking boundary conditions, loop invariants, etc. If the problem is relatively easy, not only the correctness but also the cleanness and readability of the code count.

2. The ability to think quickly and solve hard algorithmic problems. Google/Facebook/MSFT tend to ask tricky questions in their interviews. Most experienced programmers don’t think that using ACM/ICPC and algorithmic problems really test a programmer’s ability to code. However, this is a good way to see if the interviewee is clever or not (and clever people learn and adapt fast). More importantly, the coding of these problems will show how can you compact several coding tricks in, say, 20 lines of code.

Actually many problems here test both abilities, and in many cases writing correct programs with a good style weighted more than knowing the algorithmic trick to a specific problem.

Several problems in my collection are taken from a problem series by Chen Liren, link. If you read Chinese, I highly recommend this series, which contains many good questions and experience reports from real interviews.

The problem descriptions and some keywords use bold fonts.

Maximum subarray problem. This problem is so famous that it has its own Wikipedia page. It was popularized by Jon Bentley in his CACM column Programming Pearls and later collected in the book with the same name.

This problem can be solved in O(n) with O(1) space using dynamic programming. The DP solution itself is not very interesting. What interests me is two others solutions, one using a technique called cumulative sum, and the other using a more general technique -- divide and conquer.

Cumulative sum is a very useful pre-computing technique to allow O(1) range queries. It costs O(n^2) for the pre-computing thought.

Divide and conquer applies on a lot of sequence problems, including many sorting and searching algorithms. The trick is to design an O(n) merging step. In this problem O(n) merging is simple. In other problems, e.g. closest point pair, O(n) merging is non-trivial.

An extension of this problem is to find the maximum submatrix. An O(n^3) algorithm is expected.

Another variant of this problem: find two disjoints subarrays A and B such that |sum(A)-sum(B)| is maximized. Suppose A is on the left and B is on the right, for position i, we need the maximum/minimum subarray in range [1,i], and [i+1,n].

Given an array that is a rotation of a sorted array (elements are unique). The rotation of an array is to split the original array into two parts and concatenate the left part to the tail of the right part. E.g., {3,4,5,1,2} is a rotation of {1,2,3,4,5}. Now given this rotated array, find the smallest element.

Obviously we can do a linear scan and find the first number that is smaller than its left number. But linear scan costs O(n). Because the original array is sorted, it is natural to know binary search might get the running time to O(log n). In designing any binary search algorithm, it is important to prove that its correctness using loop invariant. [Bentley’s pearls and CLRS both cover loop invariant.] The algorithm sketch:

l=1, r=n

while a[l]>a[r] do

if (l+1==r) then

return r

m=(l+r)/2

if a[m]>a[l] then

l=m

else

r=m

return a[l]

Another binary search problem: given a sorted array, if A[i] == i, i is called magic index. Find the magic index.

Another binary search problem: given an array A=BC where B is a sorted array with non-increasing order, and C is a sorted array with non-decreasing order. Find B and C.

Not binary search, but incremental search: given an array A in which any two consecutive numbers diff by 1. Find the index of a target number T. E.g. A= {4,5,6,5,6,7,8,9,10,9}, and T=9.

Given an array of integers, write an algorithm that shuffles the array so that all odd numbers and ahead of even numbers.

This problem tests the understanding of quicksort algorithm. In quick sort’s partition procedure, once we fix a pivot, there is an O(n) algorithm that puts all elements less than or equal to the pivot to the left, and all elements that are greater to the right. In this problem, we shall redefine the comparison function that any odd number is “smaller” than any even number.

If C/C++ used, then write a general partition procedure which takes a comparison function pointer(C)/comparison operator(C++) as input would be nice.

A variant of this problem: 3-way partition. Given an array and i, design an in-place algorithm that puts all number < A[i] to the left, and all numbers = A[i] in the middle, and the rest in the right.

Another variant of partition algorithm: sort an array of 1/2/3 (don’t count # of 1,2,3), use a new partition algorithm instead.

Inversions. Given an array, calculates the numbers of pairs (i,j) such that A[i]>A[j].

This problem has several solutions. One is to modify the merge procedure in merge sort, to count the inversions in each merge procedure. Other solutions require using advanced data structures, and we don’t cover them here.

long long res;

void merge(int l, int m, int r)

{

int n1=m-l+1, n2=r-m;

for (int i=0; i<n1; i++) L[i]=a[l+i];

L[n1] = INF;

for (int i=0; i<n2; i++) R[i]=a[m+i+1];

R[n2] = INF;

int j=0,k=0;

for (int i=l; i<=r; i++)

if (L[j]<=R[k]) a[i]=L[j++];

else { a[i]=R[k++]; res+=n1-j; }

}

void merge_sort(int l, int r)

{

if (l<r) {

int m=(l+r)/2;

merge_sort(l,m);

merge_sort(m+1,r);

merge(l,m,r);

}

}

Majority. Given an array of n integers, find the number that occurs more n/2 times, or report that such a number does not exist. E.g., in array {1,2,2,2,3}, 2 is such a number.

Solution 1: If such a number exists, then the n/2-th number in the sorted array must equal to it. Then we can first use a linear algorithm to find the n/2-th number in an unsorted array. In the literature, this k-th number problem is called selection problem, which has a complicated linear algorithm by Blum et. al. (four of the five authors of this paper were awarded Turing award!), and a O(n)-average time algorithm using quicksort variant.

Solution 2: a property of this problem: removing any two numbers that are different -> the frequent number remains the same. A walk through of the array using this property can get a candidate of the frequent number. Another linear scan checks whether the candidate occurs more than n/2 times.

A variant of this problem is to find a number that occurs more than n/3 times. The above two solutions still apply.

Given an array of integers, concatenate all numbers in some order so that the combined string is lexicological smallest. E.g., {3,32,321}, solution is 321323.

Define a new comparison operator of two numbers and sort the array. The new comparator is

compare x y

if str(xy) > str(yx) then

1

else if str(xy) < str(yx) then

-1

else

0

The tricky part is to prove that this does yield the smallest string. To prove this order is correct, we need to prove three properties: reflexive, symmetric and transitive.

Given a sorted array and an integer x, output the number of times this integer occurs in the array.

Linear scan costs O(n). A straightforward binary search can spot the first occurrence of this integer, and we continue to count until the next number is not equal to it. However, this integer can occur O(n) times. A workaround is to do binary search again at the first occurrence. Suppose the first occurrence is at position i, and there are m numbers to the right. First, we check position i + m/2, if equal, we check i + m/2 + m/4, if not equal, we check i + m/4, and so on. However, this is non-trivial to get correct because there are a few boundary conditions.

The best solution to this problem is to use two binary search functions in C++ STL: lower_bound and upper_bound. lower_bound finds the smallest position i such that A[i]>=x, upper_bound finds the smallest position i such that A[i]>x. The solution to this problem is simply upper_bound(x)-lower_bound(x). The two functions already take care of boundary conditions and cases where x does not occur in the array.

Given an array of integers, all integers occur exactly twice except for one. Find the only integer that occurs once.

Use bit trick. x xor x = 0. (if a bit occurs twice, set it to 0)

Variant: Given an array, except for one X, all other numbers occur exactly 3 times. Find X.

Now bit trick does not work. However, the idea is the same. If a bit occurs 3 times, set it to 0.

Integers and sum. Subproblem 1: given a sorted array, find two numbers that sum to m. Subproblem 2: the array is not sorted. Subproblem 3: find four numbers that sum to m.

For subproblem 1, there is a trick called ruler reading. Keep two pointers to the left and right of the array, and move the pointers until the sum if m. O(n)

For subproblem 2, hasing or sorting.

For subproblem 3, there is trick called two-head search. First, we get the sums of all pairs (O(n^2)), sort these sums or put them in a hash table. for a+b+c+d=m, we now only need to enumerate a and b, and check whether c+d exists using binary search or hashing.

Another problem using ruler reading technique: given an array of positive integers, and S. Find a subarray with minimal length and the sum of the subarray is >= S.

Arrange 0 to n-1 in a circle, starting from 0, delete every m-th number. Output the delete numbers in sequence. E.g, {0,1,2,3}, m=2, the sequence is 1,3,2,0.

Solution: O(n), in every step, use module operation to find the exact number.

Given an array of integers, find a maximum subset that constitutes a sequence of consecutive integers. E.g., {15, 7, 12, 6, 14, 13, 9, 11}, the answer is {11,12,…,15}.

Obvious solution is to sort the numbers in O(n log n) and then do linear scan. The solution requires a running time better than O(n log n). Hint: make the consecutive numbers into same set, and use disjoint set algorithms to have O(n log log n) running time.

Given k sorted arrays, find a range [a,b] with minimal length such that each array has at least one element in [a,b].

Example,

1: 4, 10, 15, 24, 26

2: 0, 9, 12, 20

3: 5, 18, 22, 30

Minimal range is [20,24].

If we have all the numbers in k arrays sorted, and mark the numbers with labels 1 to k, then our minimal range should contain all k labels. This range checking can actually be done while we do merge sort of the k arrays. Hint: set a pointer for each array.

Given an array of 0/1, find the longest subarray such that the number of 0s and the number of 1s are the same.

Using the cumulative sum technique, the problem can be solved in O(n^2). Hint: fill 0 with -1, and use cumulative sum technique again.

Largest Rectangle in a Histogram. Given an array of heights, calculate the rectangle with largest area.

Solution: pre-compute two arrays L and R, L[i] indicates the most left position where h[L[i]]>=h[i].The following C++ code snippet calculates L (R would be similar):

int t = 0;

for (int i=0; i<n; i++) {

while (t>0 && h[st[t-1]] >= h[i]) t--;

L[i] = t==0?0:(st[t-1]+1);

st[t++]=i;

}

Many other solutions to this problem: http://www.informatik.uni-ulm.de/acm/Locals/2003/html/judge.html

Variant: Given an matrix with 0/1, find the max submatrix with only 1s.

A much easier problem: given an unsorted array A, find in linear time, i and j (j>i), such that A[j] – A[i] is maximized.

In-place shuffle array: 1, 2, 3, …, 2n => 1, n+1, 2, n+2, etc. solution: Peiyush Jain, A Simple In-Place Algorithm for In-Shu?e. http://arxiv.org/pdf/0805.1598.pdf

Coins change problem. Given an array A and X, find how many subsets of A sum to X. Solution: DP.

Given two arrays S and T. Each is a permutation of 0 to n-1. By swapping 0 and another number repeatedly, change S to T. If minimal swaps are required, how to do it?

Solution: get a position correct in every step. If minimal swaps are required, use BFS/short path algorithm.

Given an unsorted array, find the longest arithmetic progression. Case 1: keep order of the original array. Case 2: no need to keep order.

Solution:

For case 1: use this hash data structure to store the n(n-1)/2 pairs of difference:

map<int, set<pair<int, int> >

difference -> sorted set of (i,j) pairs [difference = a[j]-a[i] ]

For case 2: since the order does not matter, we first sort the array in O(nlogn), and then the longest arithmetic progression is a sub sequence of the sorted array. This can be solved by DP:

dp[i][j] = dp[j][k] + 1, if i<j<k, a[i]-a[j]=a[j]-a[k]

dp[i][n-1] = 2, for all i < n-1

Given an array of n unique numbers from 1 to n, delete 1/2/k numbers, how to identify the deleted number/numbers?

For k=1, calculate sum.

For k=2, calculate sum and sum of squares.

For k=3, calculate sum, sum of squares, and sum of cubes.

Time: O(nk)

Another solutions: count the 0/1 bit at each position. Time: O(n log n)

An array of length n+1 is populated with integers in the range [1, n]. Find a duplicate integer (just one, not all) in linear time with O(1) space. The array is read-only and may not be modified. Variation: what if the array may be written into but must be left unmodified by the algorithm?

Solution: http://gurmeet.net/puzzles/duplicate-integer/ and

The best solution requires solving several nontrivial subproblems, which are actually linked list problems!

Given an unsorted array A of n distinct natural numbers, find the first natural number that does not appear in the array.

I first saw this problem when reading R. Bird’s pearls of functional algorithm design, in which this problem is the first pearl. There are at least two good solutions (favor different tradeoffs) to this problem:

1. From 0 to n, there must be an integer that does not appear in A. We use an extra bool array with size n+1 and scan the array to mark occurred numbers. Then we can scan the bool array to find the first non-mark number as the solution. This solution is very easy to implement and costs O(n) time and O(n) space. Can we reduce the space cost?

2. Divide and conquer. Let’s check this property: from low to low+n, there must be a number that does not occur in A where low is the smallest (possible) number in A. We just need to guarantee that A does not have numbers smaller than low. Besides low, if we also know the upper bound value of A (we define upper bound as the number that is bigger than all numbers in A). So there are at most high-low distinct numbers in A. If and only if high-low==n, the numbers in [low, high) all occur in A once. If high-low>n, then there is a number in [low, high) that does not occur in A.

With this property, we can design a divide and conquer algorithm that in each step discard half of the numbers, the following is an implementation from Bird’s book:

minfree xs = minfrom 0 (length xs, xs)

minfrom a (n, xs) | n == 0 = a

| m == b-a = minfrom b (n-m, vs) -- discard the numbers < b

| otherwise = minfrom a (m, us) -- discard the numbers >= b

where (us, vs) = partition (< b) xs -- partition in quicksort

b = a + 1 + n div 2

m = length us

This method uses O(n) time and O(log n) space. But the space cost can be reduced to O(1) if we write a iterative version of the above procedure. And different from linear selection algorithm which is only O(n) on average case, the algorithm here is strictly O(n).

Two problems on permutation arrays:

Find the next permutation. This function is implemented in C++ STL. Its Wikipedia page has a solution. The following is an OCaml implementation:

let next_permutation a =

let swap i j =

let tmp = a.(i) in

a.(i) <- a.(j);

a.(j) <- tmp;

in

let n = Array.length a in

let k = ref 0 in

let i = ref (-1) in

begin

(* find largest i such that a(i) < a(i+1) *)

while !k<n-1 do

if a.(!k) < a.(!k + 1) then

i := !k;

k := !k + 1

done;

if !i = -1 then None (* if such i does not exist, no next permutation *)

else begin

(* find largest j such that a(j) > a(i) *)

let k = ref (!i + 1) in

let j = ref !k in

while !k<n do

if a.(!k)>a.(!i) then

j := !k;

k := !k + 1

done;

(* swap i j *)

swap !i !j;

(* reverse all after index i *)

let k1 = ref (!i + 1) in

let k2 = ref (n - 1) in

while !k1 < !k2 do

swap !k1 !k2;

k1 := !k1 + 1;

k2 := !k2 - 1;

done;

Some a;

end

end

Find the inverse of a permutation. E.g. A = [4,2,1,3] is a permutation, its inverse is B = [3,2,4,1], i.e. B[A[i]] = i (index starts from 1).

Solution: inverse several circle linked lists.

Problems with no good solutions yet:

Given an array A with length n, filled with 1 to n. Some numbers occur multiple times, some don’t occur. Identify these two groups of numbers in O(n) time and O(1) space.

Given an array, some numbers occur once, some twice, and only one X three time. Find X. (No solution yet)